HISTORY OF THE PLAGUE

by Portsmouth University, retired lecturer in Medical Microbiology, Tim Mason PhD

How the PLAGUE bacterium evolved

PLAGUE. It really does deserve to be in capital letters, as this horrific and often lethal disease PLAGUED the world for centuries, and still does in some places. Indeed, there was an outbreak in Madagascar, with at least 2348 cases as recently as August 2017, which led to 202 deaths (see WHO report)

What we learned from Tim Mason’s dynamic lecture was that the bacterium responsible for the plague — Yersinia pestis — only appeared 3,000 years ago. Prior to that date a close relative existed from which plague probably evolved. Yersinia pseudo-tuberculosis is the name of that more ancient foe which still infects the gastrointestinal tract today, often via poorly cooked meat products. Unlike plague, however, it is not usually life-threatening, causing only fever and abdominal pain.

It is thought that a key step in the emergence of plague occurred when, three millennia ago, the bacterium evolved a new enzyme called ‘plasminogen activating factor’, which made the resulting species Yersinia pestis far more virulent. Yersinia pestis can be passed by several routes and infect different organs: bubonic plague is spread by flea bites, affecting the blood and lymph; septicaemic plague is the rarest form; whilst the deadliest of the three, pneumonic plague, is transmitted by air-borne droplets (coughing) where it infects the lungs. All three forms of the disease are caused by the same bacterium.

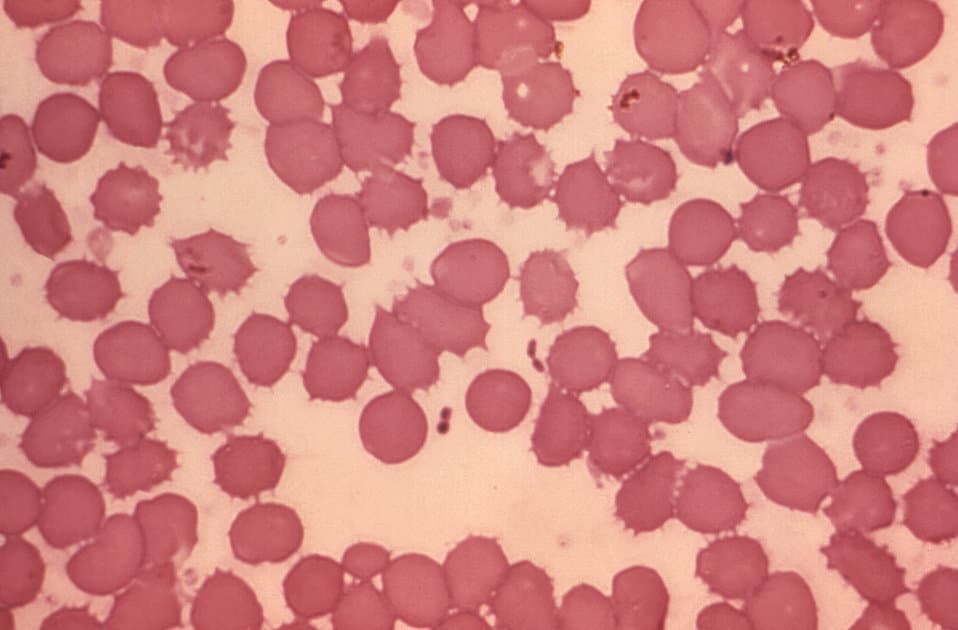

This is a micrograph of a blood smear containing Yersinia pestis plague bacteria. (Public Domain)

One characteristic common to all Yersinia species is the ability to attack phagocytic cells, a crucial part of the host response to pathogens, which explains its infectivity.

Pneumonic, or respiratory plague began in around 2,800 BC some 3,000 miles east of Moscow, in a minuscule place called Bateni, and it arrived in Moscow a couple of hundred years later via the Yamnaya herdsmen. In researching the Yamnaya I was surprised to find that plague was not the only thing they introduced to the West…

Once plague arrived, it was not long before the first major outbreak occurred. In 541 AD, ‘The Plague of Justinian’ as it was known (due to occurring in the Emperor Justinian’s reign, rather than because it was his fault) led the end of the Age of Splendour, precipitating the decline of the Byzantine Empire. In the period leading up to the outbreak, there had been a huge increase in the size of the Byzantine population; but with extended trade and increased movement of people came disease, in a truly devastating form. At its peak, 5,000 people died every day in Constantinople, culling the city’s population which was finally reduced to less than half of its pre-plague numbers.

In total, around 25% of the Eastern Mediterranean population are thought to have succumbed to the pestilence. Frequent waves of plague struck throughout the 6th, 7th and 8th centuries, though these were more localised and less virulent.

The ‘Second Pandemic’ arose in China in 1200, and modern DNA techniques have shown us how it spread. The Mongol Hoards played a major part, but the research now implies it went via the sea routes, rather than overland via the Silk Road as previously assumed. It appears to have made its presence felt in all the ports of eastern, then western India, up and down the Persian Gulf and Red Sea, then overland to Turkey in 1347 where it rapidly spread onwards.

The first case of the Black Death (plague) in Britain was noted in Weymouth on the Dorset coast on July 7th 1348 from where it went on to infect and kill up to half the population of Weymouth; From there it spread to Titchfield, where Bishop Edington described it in October that year as ‘this cruel plague’. Many of the large Estates ceased to function due to the loss of life and manpower, so normal commercial and social society, at all levels was seriously impacted.

That same year Pope Clement VI, one of the Avignon Popes, wrote a Papal Bull to halt the pogroms that had erupted throughout Europe against Jews, who were being blamed, falaciously, for spreading the plague by disconsolate populations. He also proclaimed that all those who died from plague would have their sins forgiven, and certainly achieve Heaven. This must have relieved not only the dying but the priests who were performing the Last Rites along with those caring for the sick.

No effective treatments had been found, though many were tried from the ridiculous (such as eating powdered emeralds) to the more reasonable (herbal medicines) from which the fashion of carrying a scented posy of flowers or a pomander arose. I had been led to believe that the nursery rhyme ‘Ring-a-ring of roses’, harks back to the plague but that interpretation of the song’s origins has now been questionned. Below are some other 13th century ‘cures’.

| Vinegar and water treatment | If a person gets the disease, they must be put to bed. They should be washed with vinegar and rose water |

| Lancing the buboes | The swellings associated with the Black Death should be cut open to allow the disease to leave the body. A mixture of tree resin, roots of white lilies and dried human excrement should be applied to the places where the body has been cut open. |

| Bleeding | The disease must be in the blood. The veins leading to the heart should be cut open. This will allow the disease to leave the body. An ointment made of clay and violets should be applied to the place where the cuts have been made. |

| Diet | We should not eat food that goes off easily and smells badly such as meat, cheese and fish. Instead we should eat bread, fruit and vegetables |

| Sanitation | The streets should be cleaned of all human and animal waste. It should be taken by a cart to a field outside of the village and burnt. All bodies should be buried in deep pits outside of the village and their clothes should also be burnt. |

| Pestilence medicine | Roast the shells of newly laid eggs. Ground the roasted shells into a powder. Chop up the leaves and petals of marigold flowers. Put the egg shells and marigolds into a pot of good ale. Add treacle and warm over a fire. The patient should drink this mixture every morning and night. |

| Witchcraft | Place a live hen next to the swelling to draw out the pestilence from the body. To aid recovery you should drink a glass of your own urine twice a day. |

Plague persisted in England for 350 years

According to Wikipedia, by the end of 1350, the Black Death subsided, but it never really died out in England. Over the next few hundred years, further outbreaks occurred in 1361–1362, 1369, 1379–1383, 1389–1393, and throughout the first half of the 15th century An outbreak in 1471 took as much as 10–15% of the population, while the death rate of the plague of 1479–1480 could have been as high as 20%. The most general outbreaks in Tudor and Stuart England seem to have begun in 1498, 1535, 1543, 1563, 1589, 1603, 1625, and 1636, and ended with the Great Plague of London in 1665.

The Great Plague of London, 1665

When plague gripped London in 1665, 1000 people were dying each week.

This is a Bill of Mortality for London in 1665. It records 63596 deaths due to plague. (Source, Wikimedia)

350 years later an article from The Royal College of Physicians remembered the role of physicians during that dreadful year:

“In May 1665, the Privy Council asked the Royal College of Physicians to publish advice about how to prevent the spread of the disease and how to treat infected people. Writing in English, and selecting remedies for people of all financial means, the authors clearly intended the book to have a wider audience than only physicians or other learned men. Many, if not most, of the recipes were based on plant ingredients commonly used at the time in apothecaries’ shops, but also available to the general population.

The physicians’ plague advice mentions many specific plants thought to be beneficial in preventing infection, such as these recommendations for perfumes:

Such as are to go abroad, shall do well to carry Rue, Angelica, Masterwort, Myrrhe, Scordium, or Water-germander, Wormwood, Valerian, or Setwall-root, Virginian-snake-root, or Zedoarie in their hands to smell to; and of those they may hold or chew a little in their mouths as they go in the streets.

The book includes many recipes for medicines to be taken internally, often with emphasis placed on the benefits of sweating. Section 21 comments that ‘the poison is expelled best by Sweating, provoked by Posset-ale, made with Fennel and Marygolds in winter, and with Sorrel, Bugloss, and Borage in Summer’. Other common ingredients were wood-sorrel, rosemary, scabious and butterburr (which was so strongly associated with plague that it had the alternative common name of ‘pestilence-wort’).”

The story of the village of Eyam in Derbyshire was well recorded at the time and tells a tale of happenstance, tragedy and sacrifice. Cloth for a wedding was sent the 164 miles from London to the local tailor in Eyam in 1665. Within a week the tailor’s assistant was dead of the plague, conveyed by the fleas who were stowaways in the cloth. The villagers, realising that the chance of spread was extremely high, and with a discussion with their vicar, applied significant precautions to reduce the risk of spread.

Families buried their own dead; church services were held in a local natural amphitheatre, allowing much more space between families; and then the whole village was quarantined, such that no one could leave and no one was permitted to enter the village boundaries at all. Over the 14 month course of the outbreak around half of the population survived, but 273 died of the plague, according to the Eyam church record. Some who were exposed survived, including the unofficial gravedigger, even though he handled many infected bodies and a mother who buried six of her children and her husband in an eight-day period, but made it through herself. They showed Britain just how to do quarantine properly!

In the end the plague was halted by the only means that ever worked (until the advent of potent antibacterials that is) which was through strict isolation of any household, and eventually any village, that was affected.

The Black Death left 20 – 50 million Europeans dead in its wake and ran from 1347 to 1720, but it is still not entirely clear what brought about its end. The strict application of quarantine, the deployment of rat catchers, better nutrition and housing, with more bedrooms leading to less close contact between family members, and probably the mini ice age that occurred would all have played their part.

This mini ice age reached its peak in the mid 17th century, and the very worst freeze on record was the 1683-84 winter when the Thames ice was 11 inches thick (28cm). This must have been a threat to life to both rats and fleas (as well as humans of course, as cold weather is far more of a killer than warm).

Plague persists in to the 20th Century

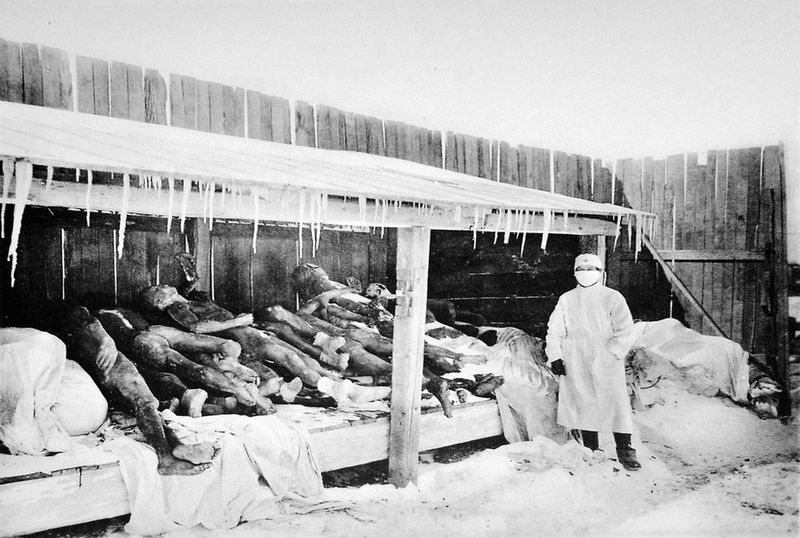

There was a third bubonic plague pandemic which started in Yunnan province of China in 1855. It spread through the world and killed over 12 million people (10 million in India alone!) and it was not declared over, by the World Health Organisation, until 1959, by which time there were only 200 annual casualties worldwide. This is a photo, taken from Wikipedia, of plague victims in Manchuria in the winter of 1910-11. Looking at those icicles I am not convinced that the mini ice age in England was responsible for the ending of our Great Plague, as it does not appear to have stopped it in China.

Swiss physician Alexandre Yersin, 1863 – 1943, who had worked with Louis Pasteur in the 1890s, was sent to Indo-China to investigate this 3rd Pandemic, and identified the causative agent as a bacillus, with a rod shape, and though he and others tried numerous times to devise a vaccine to prevent this deadly disease, they were unsuccessful up to the present day. The only effective treatment has been, for over 70 years, specific antibiotics, but the disease has not fully disappeared. In the 21st century, shockingly, many countries in Africa and America have had small outbreaks, with 1,000 – 2,000 cases per year in total. This includes some in the USA too, especially New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, California, Oregon and Nevada. However, in the past five years, the main hot spot for plague has been Madagascar. Indeed there was an outbreak in 2017 in this island off the south-east coast of Africa, where the highly contagious pneumonic form is at work.

There is some concern that Yersinia pestis could be used in germ warfare, indeed the Tartar warriors used to sling dead plague victims over the walls at the Siege of Caffa in Crimea in 1346, so they were certainly part of the early spread of the Black Death. In the Sino-Japanese war of 1937 – 1945 the infamous Imperial Japanese Unit 731 are thought to have used plague-infected fleas against the Chinese, amongst other horrendous acts of barbarism, so the fears of germ warfare potential are not without foundation.

Thank Goodness that we now have streptomycin, gentamicin, doxycycline, or ciprofloxacin to treat this horrendous infection, and long may these continue to be viable, and NOT misused such that plague develops an antibiotic-resistant form. That would be hell indeed.

This absorbing lecture was presented to the West Sussex History of Medicine Society in 2017

Post written by

Afifah Hamilton MNIMH

Consulting Nutritionist, Medical Herbalist & owner of Rosemary Cottage Clinic